Multifamily Housing Study Story

As architects we are, like everyone, recalibrating our normal and asking ourselves: how can we do our part to address the health crisis that has defined our time. Architecture and design have constantly pivoted and evolved in reaction to an era’s extraordinary forces. Cholera, tuberculosis, and flu pandemics of the past two centuries have informed our built world in all sorts of seen and unseen ways; from the public park movement in the 1830s to the grand windows and unornamented walls of modernism—our built environments have been shaped and reshaped, time and again, in response to health crises in our developing world. We know that this time will be no different. And so when we were approached to put together this study on how multi-family housing might be newly shaped by this pandemic we leapt at the chance. Like everyone, we are paying the closest attention to the most current guidelines set out by our dedicated colleagues in the medical establishment. And we know that the science on the spread of COVID-19 is far from settled. Given what we’ve learned so far from the successes of spacial interventions like social distancing and partitioned movement, we see that architecture and design have a vital role to play. And so it is our industry’s imperative to lend our expertise. What follows are a brief set of ideas and guidelines on how slight, but consequential, design adjustments can aid in our society’s action against not just this virus, but the future unknowable ones sure to follow.

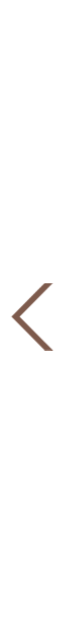

Previously we might have approached a multi storied housing project with a central lobby at the ground level with a single elevator bank servicing all floors and with occupancy programmed at the ground level.

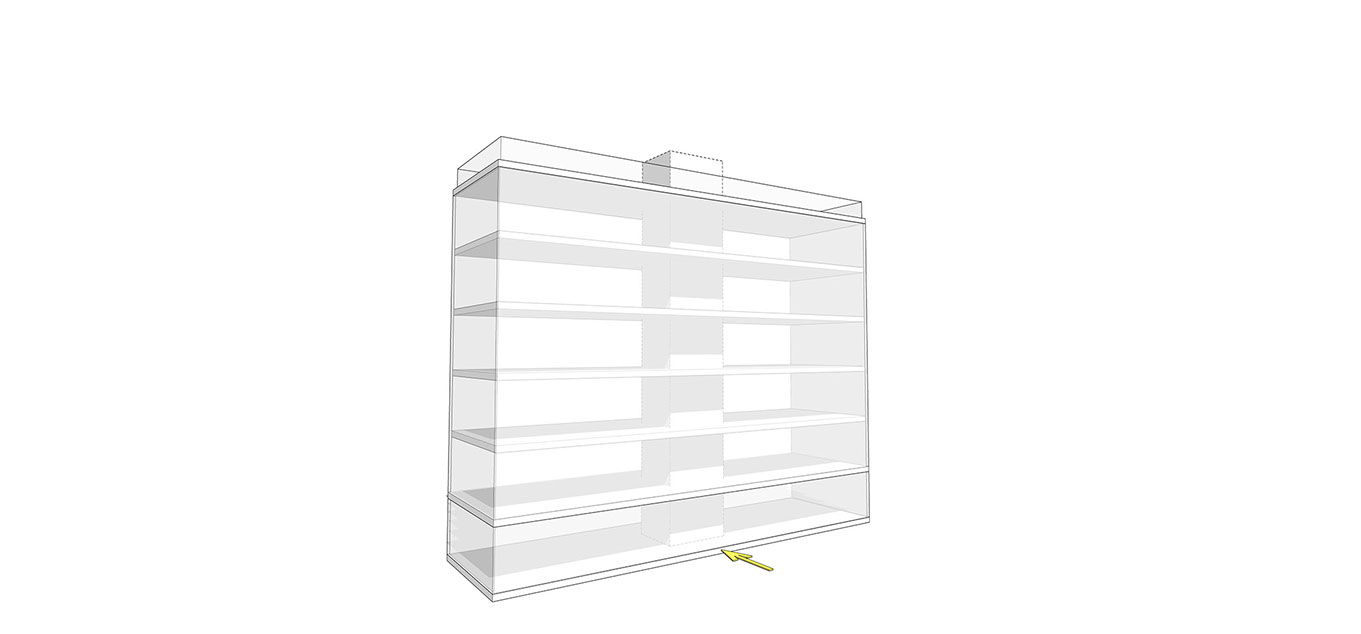

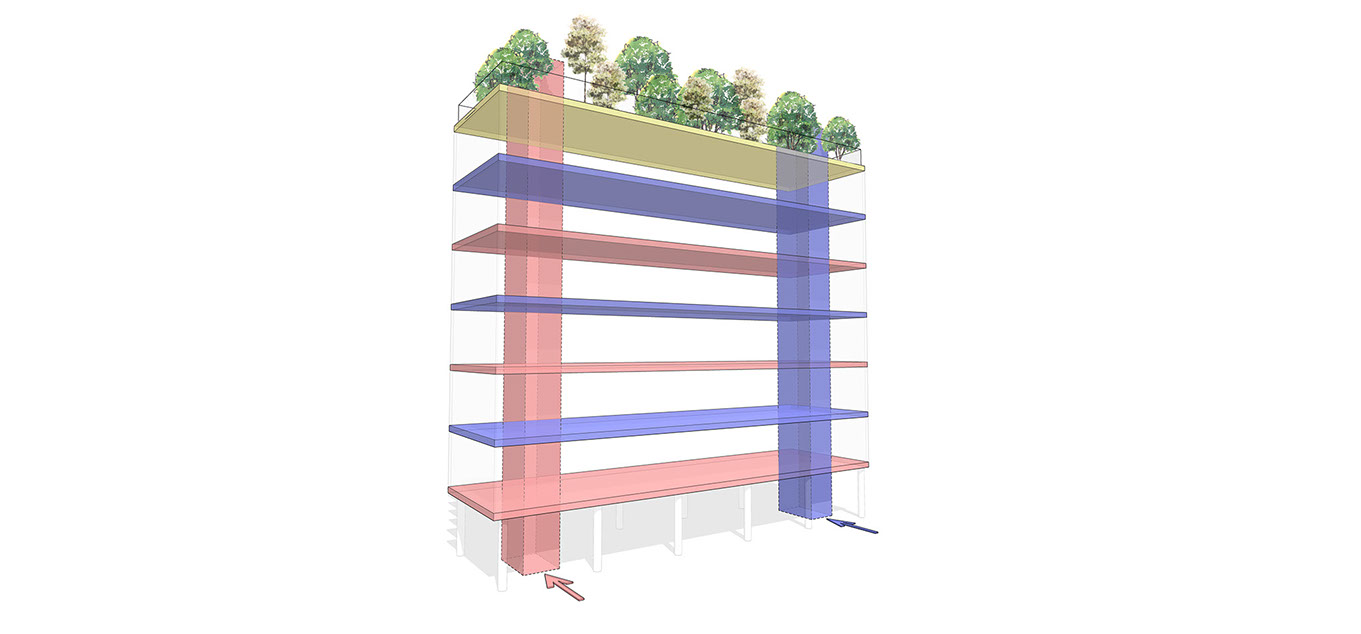

Considering the necessary spatial interventions, we suggest raising the occupancy above grade (with either parking or common area beneath) to keep tenants a step removed from public pedestrian traffic.

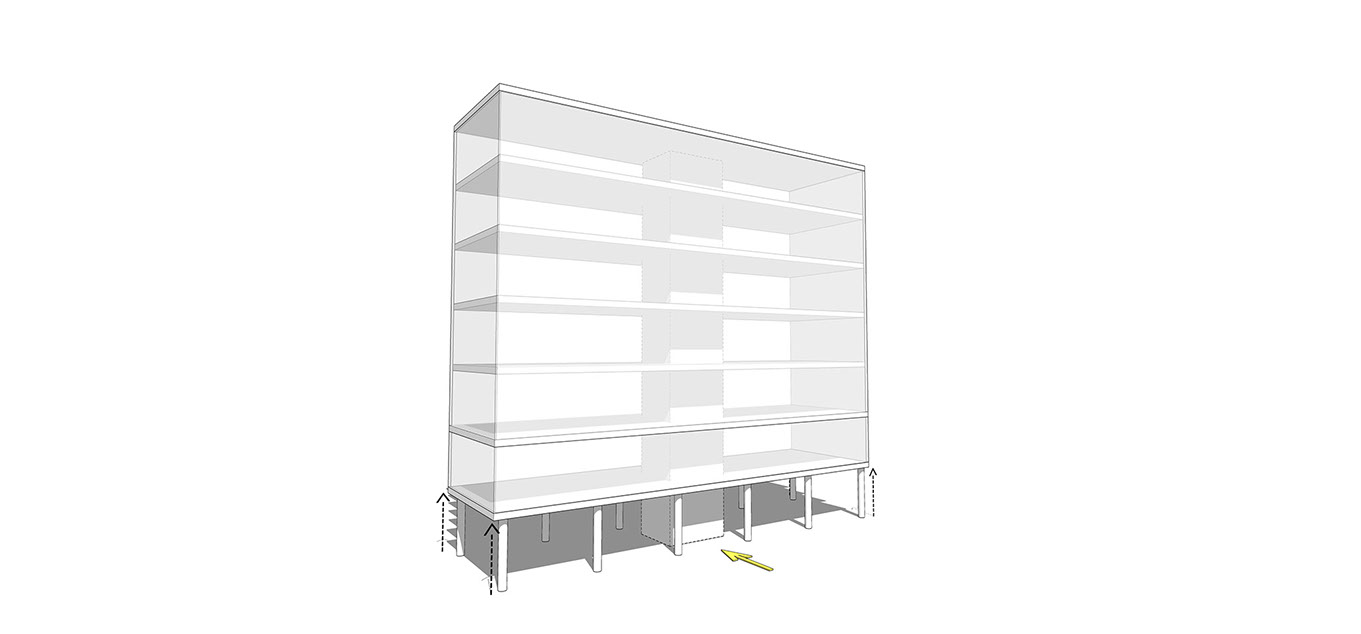

In the service of partitioned traffic circulation we imagine two entry points at opposing sides of the building, with two separate elevator cores serving specific floors. By doing so we can reduce traffic interaction by 50%.

We imagine a more in-depth access control system to further partition circulation. Elevators would be floor specific with tenant-access to home floor and common areas, effectively assigning half the occupancy to one elevator and half to the other. We suggest Radio Frequency Identification (or RFID) as programmable access controls in lieu of keys or keycards. As our telephones all become equipped with RFID we see this as a clear, contact-less system for people-moving within buildings.

We’re rethinking our project’s transitional spaces. Here in one of our studies we’ve programmed outdoor hallway space for fully ventilated pathways.

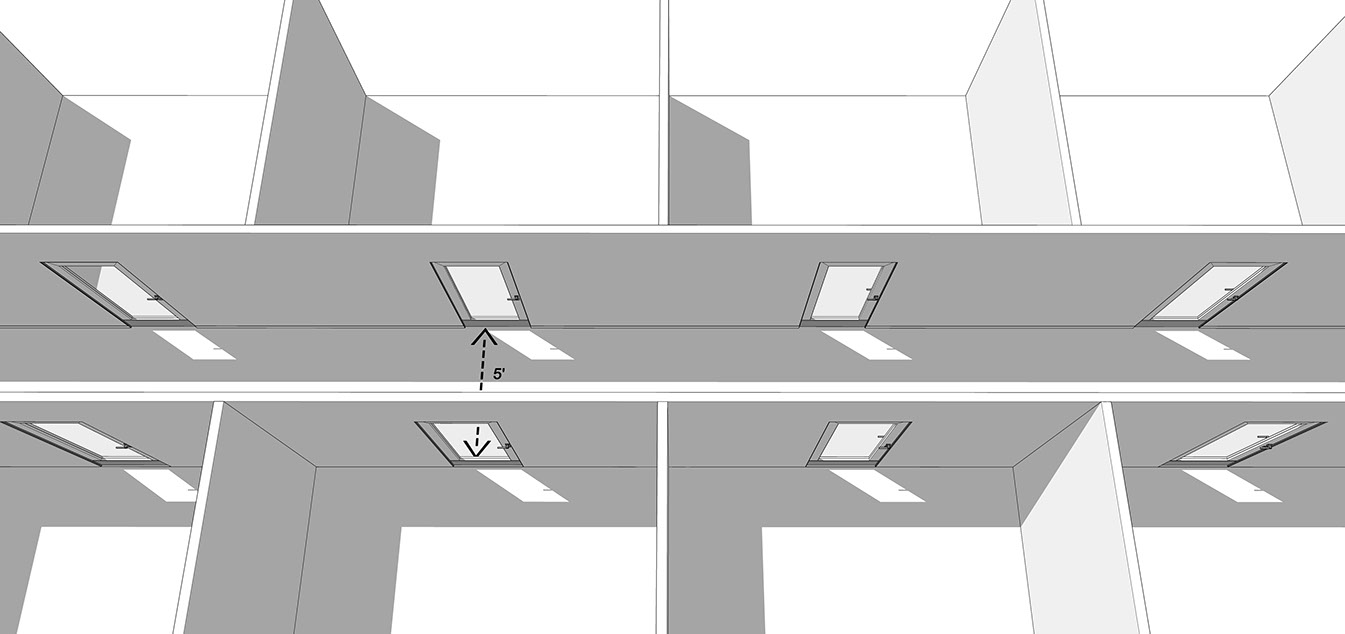

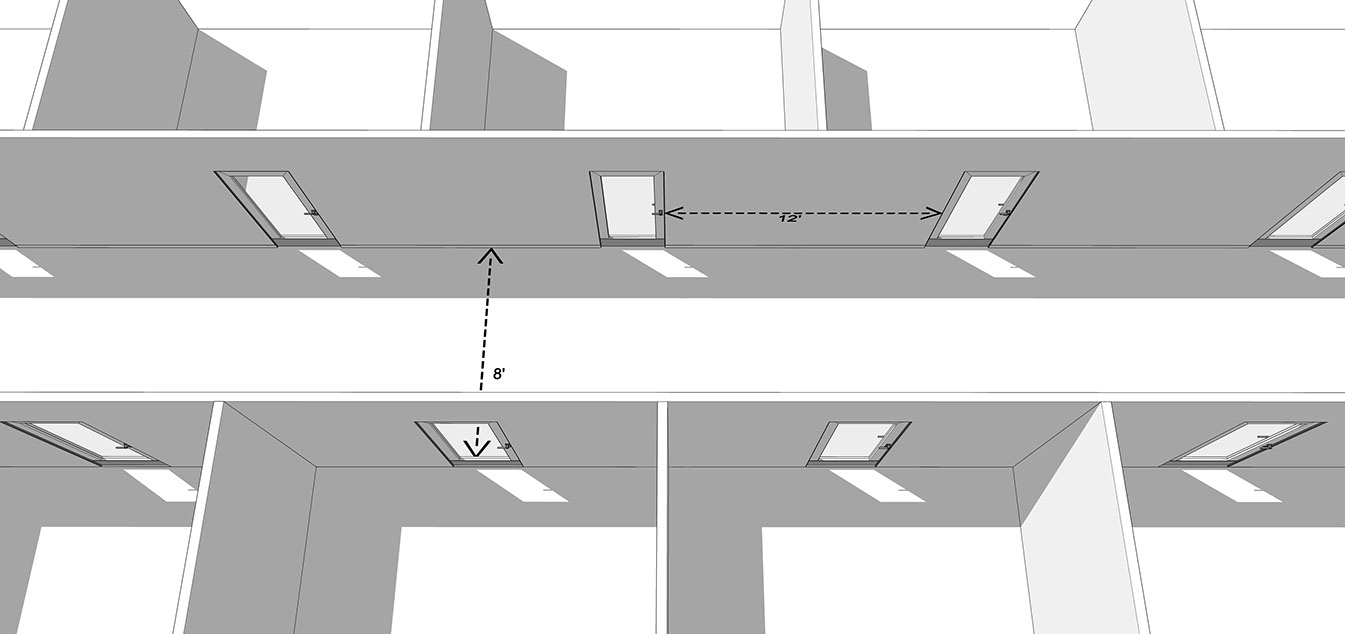

For interior pathways we imagine widening corridors to a minimum of 8 feet to more easily accommodate cross traffic.

After an initial widening in the hall we place apartment entries at a minimum of 12 ft apart while offsetting with opposing entries by a minimum of 6 ft to again limit unnecessary cross traffic.

In both studies we specify floor-to-ceiling windows with operable sections for critical air movement, disinfecting UV rays and of course full light.

Whereas higher-end housing almost always has amenities on site we’re suggesting that general housing also work to include them in their budgets. We suppose partitioned play spaces, controlled pool access by timed RFID scheduled access, and a roof top garden space with family-sized congregating spaces carved out by design. With access to amenities provided on site, building occupants can reduce their reliance on more crowded public facilities limiting broader communal exposure.